Telstra’s latest downgrade has prompted another outpouring of critisism from market participants. Given a share price that is 15% below the 1997 IPO price, these are easy barbs to throw. In this piece I want to speak in defence of Telstra. Not in the specifics, because like everyone, over this 20 year period they have made plenty of mistakes. A few of the more notable being:

- Dotcom era exuberance – Solution 6, PCCW, etc

- Delayed sale of Yellow Pages and Trading Post Acquisitions

- $1.5bn buyback at ~$4.50 in 2016

In addition, the recent handling of the dividend cut and guidance has been poor. Given the visibility and materiality of NBN payments the forward earnings hole and its impact on dividends should have been confronted much earlier.

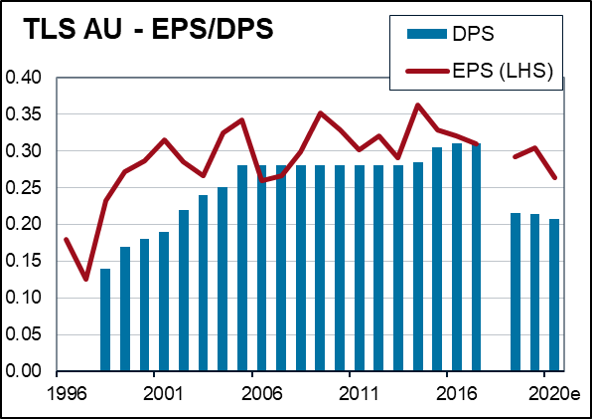

Nevertheless, it is the dividend policy that I want to defend, particularly against the criticism that the high payout ratio is somehow behind the problems.

The Telstra Dividend Dilemma

One of the complaints about Telstra is that in an attempt to prop up the share price, they have paid out too much in dividends rather than reinvesting in the long term health of the business.

Certainly, the truth of a high dividend payout cannot be denied. But what I want to argue is that this policy has been both correct from a capital allocation point of view and a good outcome for shareholders.

The Wisdom in Telstra’s Capital Allocation

Don’t get me wrong, Telstra’s capital allocation hasn’t been perfect. I’ve highlighted above a few of the howlers, the 2016 buyback in the full knowledge of the NBN payments profile possibly taking the cake.

But in a general sense, the capital allocation policy has been one of paying the majority of free cash flow back to shareholders. To the extent that there has been investment, the vast majority of this has been back into the domestic business, particularly mobiles. I think this policy has been correct, for the simple reason that there has been nowhere else worthwhile to put the money.

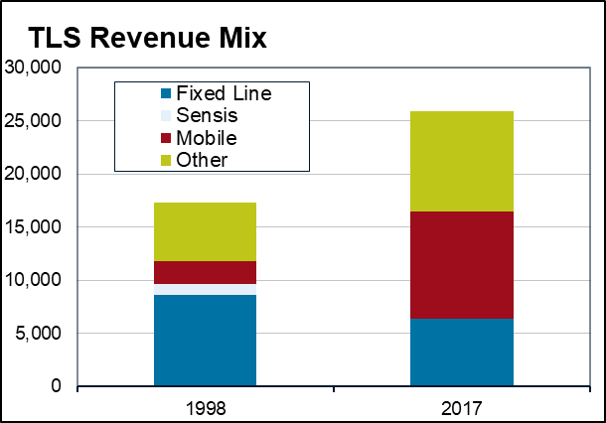

Telstra then and Now

Few other companies on the exchange have had to endure as much regulatory and technological change as Telstra has over this period. From the revenue base at listing, well over half has either been regulated away or made obsolecent by technology. The share of profits would be much higher.

Yet despite this, Telstra has managed to maintain market leadership in mobiles (market share ~40%) and fixed line nbn (~50%). Given the regulatory changes in these industries, this is a very credible long term result. Returns have declined, but not catastrophically so – although there is clearly more pain to come on this front.

Telstra – The Alternatives

Of course in any historical analysis, the key question is not what did happen, but what else could have happened. What else could Telstra have done?

The counter argument seems to be that Telstra should have retained more of its cash flow to invest in improving its long term growth. But where?

As noted, the big area of investment was mobiles and in this space Telstra has to date done exceptionally well. It has market leadership in both revenue and earnings. With competition continuing to increase, there is plenty of room for Telstra to falter going forward, but if they do this won’t be due to a lack of past investment.

Where else could they have invested? Offshore? Relatively small efforts in these areas have met with mixed results. Surely investors wouldn’t want Telstra forking out large sums on geographic expansion – Phillipines mobile? Adjacent products? Surely we wouldn’t want an already complex business further stretched by major acquisitions into adjacent areas – Free to air TV? New technologies? Ooyala and Telstra health are probably enough evidence of where this strategy might have led at scale. There is a legitimate argument that more could be done to improve customer service and efficiency. This is true, but the errors on this front seem to be largely ones of execution rather than capital allocation.

I’d argue that broadly, Telstra has done what we expect companies to do when they are faced with limited high returning investment opportunities. Return the cash to shareholders and let them find the investment opportunities. Given franking credits (and the often overvalued Telstra share price), dividends has been the best way to do this.

The surprising thing about this is that for Telstra shareholders its been profitable.

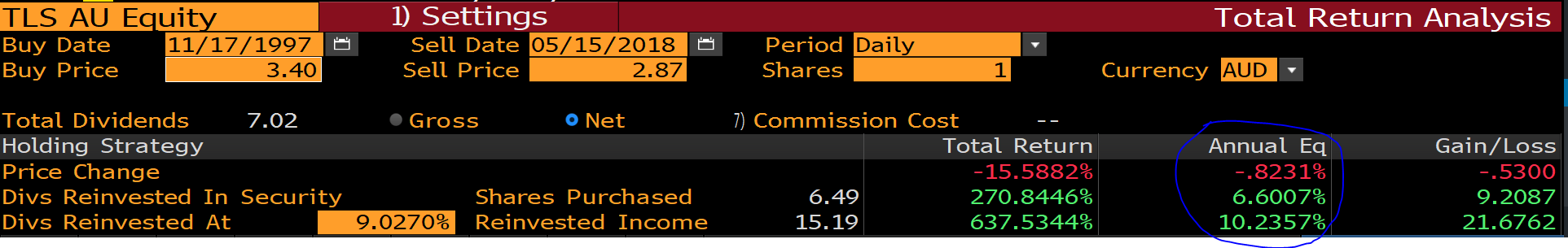

Telstra Accumulated Returns

Its obvious that Telstra shareholders have done better than the share price suggests. Its just not clear how much better they have done.

The Snaphot below highlights the total return to investors who purchased shares in the inital T1 float. Like most TSR analysis, you have to make an assumption about what happens to the dividends that get paid out. The standard assumption that is made is that dividends get reinvested in the share price. Under this assumption, T1 investors have made 6.6% per annum, signifiantly underperforming the ASX 200 Accumulation Index.

However, whilst this assumption is theoretically correct and convenient for those calculating TSR, I’d argue that it is practically wrong. The whole point of the Telstra dividend policy is that Telstra don’t think they have anywhere better to invest the money. They give it back to shareholders so that they can spend or invest it ELSEWHERE. In the below analysis I’ve assumed that they invested it back into the ASX 200 rather than back into TLS. By reinvesting it at 9% pa in the index, their TSR over this period rises to 10.2%. On this basis, TLS investors have outperformed the ASX by >100bps per annum over the last 20 years. How many fund managers who have criticised Telstra could lay claim to this track record? Note that this analysis assumes net dividends. For those able to take advantage of the franking credits, returns have been even better.

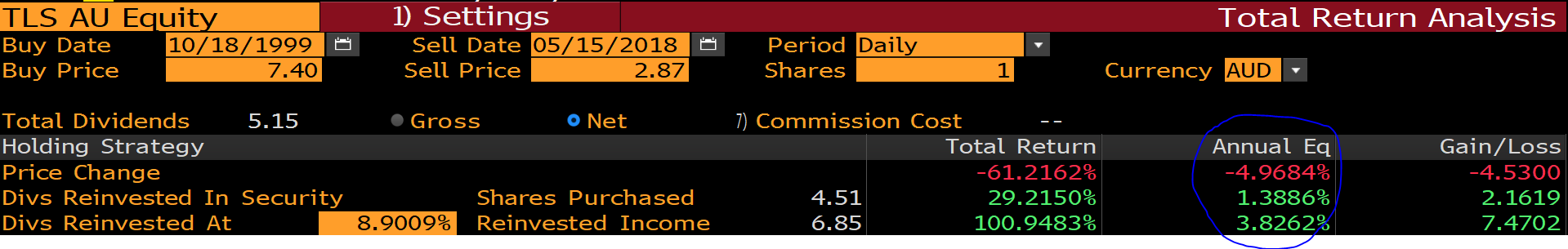

Returns for investors in T2 have not been so good. Even reinvesting dividends back into the market has only delivered 3.8% pa. – well short of the index return of 8.9%. But this can hardly be blamed on Telstra paying dividend. It lies with investors buying telco shares at the peak of the TMT boom. One can only imagine the pain if Telstra had invested even more heaviliy in growth at this time. The deals they did do were bad enough.

Investors in T3 have fared less well in an absolute sense, but very well in a relative since. If they chose to reinvest back into the index, they have outperformed the index by ~130bps over the last decade. Again a record that most fund managers would be proud of. Remembering that this has occured at a time when competition, both in mobile and via the nbn, has been at its fiercest.

Conclusion

The point of this post is not to argue that Telstra has been a great investment. Clearly it hasn’t – major changes in both technology and regulation have seen a steady erosion of historic monopoly profits. Its also not meant to be a defence of current management, the strategy of buying on yield or a recommendation at current prices. Finally, its not a view on what should happen to the dividend going forward.

Rather, the argument I want to make is that over the last 20 years I think the Telstra board have broadly done the right thing in maintaining a high dividend payout. They have taken the steadily declining stream of monopoly profits, invested the majority into mobiles with great success, given the next biggest part back to shareholders and at the margin invested in a few new products and geographies with fairly mixed success.

Investors have been given the opportunity to take this cash and invest it elsewhere. If they did this merely be investing in the market, their overall outcomes have been good. Of course this doesn’t apply to every purchase of Telstra, much as it doesn’t apply to any purchase price of any company.

Investors who criticise Telstra for paying high dividends, really only have themselves to blame if they haven’t put these dividends to good use. I suspect that had the alternative occured and Telstra invested heavily in trying to win the future, then the blame being heaped on Telstra would likely be much more severe and justified.

If other mature companies had the sense of Telstra to return surplus cash to shareholders rather than trying to chase elusive dreams, perhaps the abnonrmal losses disclosed every reporting season would require a lot less ink.