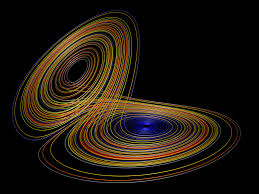

A useful model from the Systems Frame is the distinction between the volatility within a system and the stability of that system. A system may be volatile in output, but stable in nature (or vice versa). A particluar type of system instability is known as a regime shift (or phase transition), where the system has a tendency to switch suddenly between different states – a classic example being the transition from water to ice (or steam). We have previously discussed these concepts in more detail here.

We can apply these models to the analysis of Challenger Group (CGF).

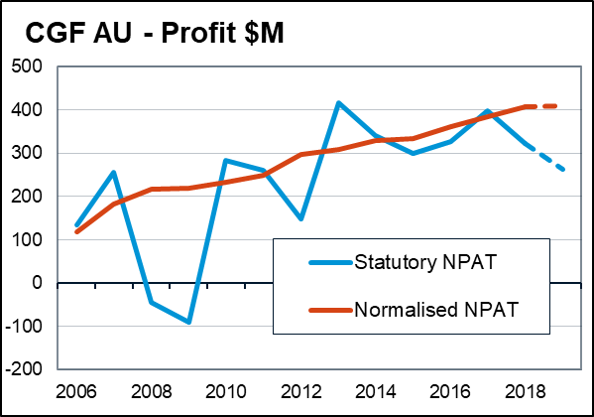

The recent profit update highlighted the ongoing dichotomy between the company’s preferred measure of ‘normalised’ earnings – which shows steady growth – and the much more volatile statutory earnings, which reflect swings in ‘investment experience’.

In essence, Challenger would have investors believe that underlying earnings demonstrate the stability of the system, whilst the swings in investment experience are simply short term volatility within the system. To the extent that the underlying system is stable, these normalisation adjustments are probably helpful for investors. They provide a rough indication of through the cycle earnings.

However, does the volatility of statutory earnings hint at something more than just a system with noisy outputs. Is this system itself inherently unstable?

The Challenger Business Model

Challenger is a very complex business, which I do not profess to understand in minute detail. However, the main driver of value is the annuities business, which works roughly as follows:

- Challenger take money from investors in return for paying them a promised rate of return.

- Challenger invest this money.

- To the extent that they invest this money at rates of return higher than promised, they can pocket the difference as profits for shareholders (and staff!).

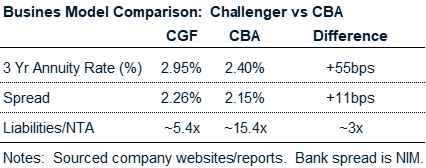

This business model is similar to the banks in concept, but quite different in execution.

We can distinguish between the two models by noting:

- Challenger pay investors a bit more than banks to access their funds;

- Despite paying more for funds, they generate higher returns on these funds for shareholders (and staff);

- These higher returns reflect the fact that the things they invest in are generally riskier.

- As such, APRA requires them to be less leveraged than the banks.

Simply – it’s a version of the higher return for higher risk trade off that’s common in finance.

How Risky are the Challenger Investments?

The difficulty for all parties (APRA, Challenger, investors in Challenger Annuities and investors in Challenger shares) is working out whether this risk/reward trade off is appropriate. Challenger, APRA and many other parties in this chain present a case that this risk is not only appropriate, but somehow measurable. APRA in particular have developed a detailed process for working this out – called APRA LPS110 Capital Adequacy. Amongst other things this includes fancy formulas designed to give the idea of certainty, such as:

As I said at the start, I’m not smart enough to understand all this detail. However, others who are have demonstrated the unreliability of such models both in theory (for example) and in practice (my favourite).

When it comes to understanding this risk as it applies to Challenger, the following thoughts are worth bearing in mind:

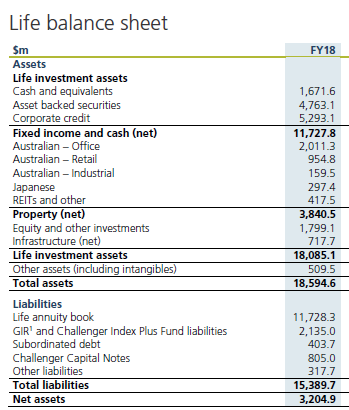

The Challenger Annuity book is invested in ~A$18bn of assets, backed by around $2.7bn of tangible equity. This represents a leverage ratio of roughly 6.5 times.

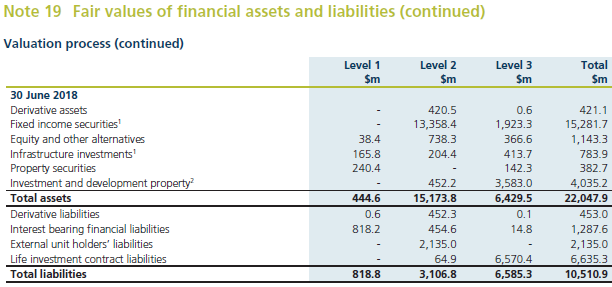

The assets are spread across a wide range of categories, but with this sort of leverage, an error in valuations of 15% would wipe out equity.

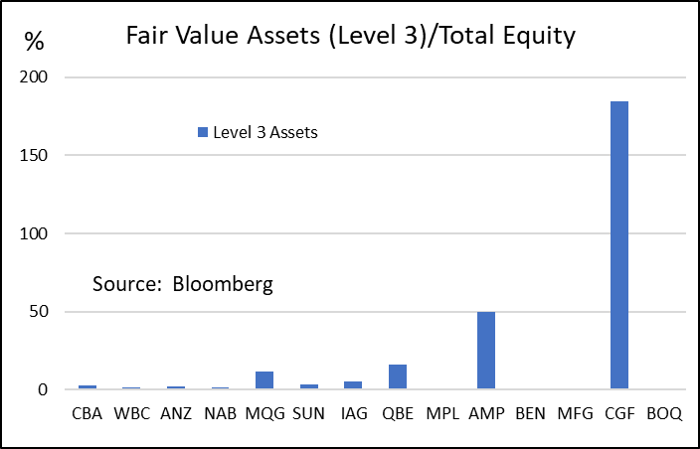

The vast majority of these assets (and associated liabilities) are valued by methods other than exchange based prices. The accountants refer to these valuations as either Level 2 (where an input in the valuation process is traded on the market, but the instrument itself does not) and Level 3 (where unobservable inputs are used). As we have written about previously here, all valuations are stories. However, some stories have more foundation than others. It is generally accepted that Level 3 stories are more subjective than Level 1 stories.

To put these valuations in context, Challenger has by far the highest ratio of Level 3 valuations to equity of any of the major Australian financials.

Level 3 valuations amount to almost 2.5x tangible equity of the life book.

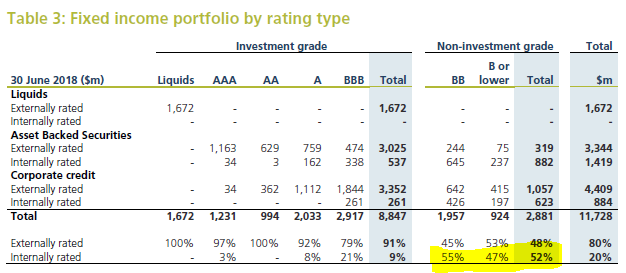

Another way of looking at these investments is by their investment rating. For example, $2.9bn (~100% of life equity) of the fixed income portfolio is rated as non-investment grade.

.

Adding to this picture is that roughly half of these non-investment grade investments are rated internally.

A final point is that many of the assets in this book represent the equity slice of the investment, not the gross value. For example, there are $1.8bn of equity and $3.8bn of property investments that are valued net of debt. It is not clear what the additional ‘off balance sheet’ gearing is in these investments. Needless to say it introduces another layer of uncertainty into the asset valuation process.

To summarise, there is a large pile of assets that:

- Yield high rates of return (so are probably above average risk);

- Are either illiquid, or internally valued, or both;

- Are leveraged >6x on balance sheet with an indeterminate amount of additional off balance sheet debt.

Stable or unstable system?

I should stress at this point that nothing in the above suggets there is anything untoward about the Challenger investment process or accounts from an accounting perspective. The point I am trying to make is:

- All valuation is uncertain;

- The Challenger assets contain lots of asset classes that have more potential for errors in their valuation than others;

- These assets are leveraged, so the impact of any errors is magnified.

Despite these issues, for most parties involved with Challenger, there is a natural tendency (or legal requirement) to try and come up with a specific valuation – both of the assets and the share price. But I would argue that this is the wrong approach. What is needed is an understanding of how stable these valuations are and in what conditions.

As noted above, one hint of this stability is the volatility of statutory earnings due to “investment experience”. Challenger imply that this investment volatility can be ignored – with the focus on underlying earnings – on the basis that the assets will be held to maturity.

But what if this is not the case? What if Challenger becomes a forced seller? In this scenario Challenger will be forced to crystallise the existing experience losses, and also perhaps to recognise some new ones as unlisted level 3 assets are revalued,via sale, into a potentially unforgiving transactional market.

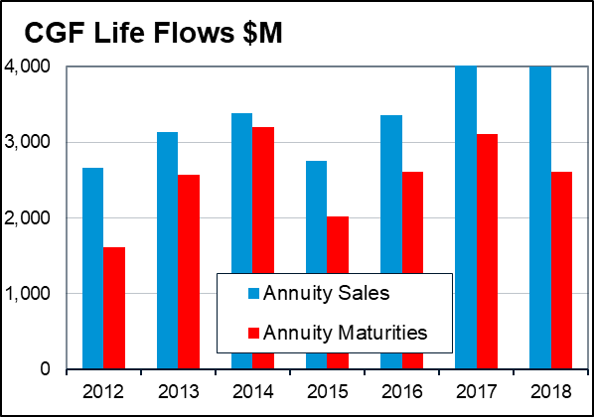

The key to this of course is whether Challenger is a net buyer or (forced) seller of its assets. This all depends on flows.

At present annuity inflows exceed outflows. Challenger remains a net buyer and can hold to maturity any bonds that are currently trading below book value and avoid selling unlisted assets that might recognise additional losses.

But what if there is a regime shift with respect to annuity flows? What if investors turn off Challenger annuities in favour of less risky options? In this case, small errors in valuation have the potential to multiply. This in turn will likely impact flows as well as book value – a double whammy for the share price.

Conclusion

Leveraged companies like Challenger resemble a Strange Attractor. In these situations, rather than there being one ‘central’ equilibrium value, there are two quite distinct attracting equilibria, with the system capable of rapid shifts between these ‘attractors.

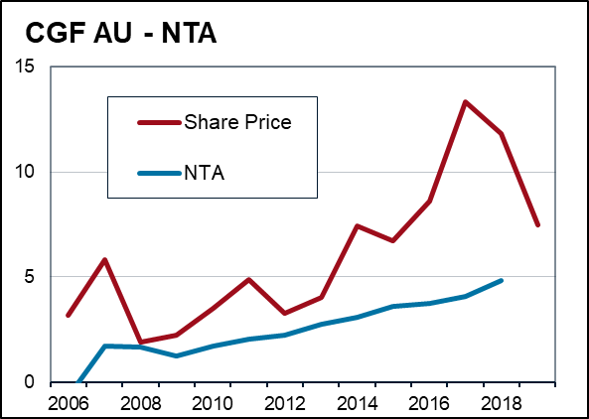

To put this in an equity perspective, there is not one fair valuation, rather, there are two approximate valuation regimes.

One of these is when Challenger is in the ‘good’ regime, where annuity inflows are greater than outflows. In this regime the positive earnings spread can be valued by the market.

The other, is when Challenger is in the ‘bad’ regime. Outflows are greater then inflows and the company is a forced seller of assets with potential negative implications for both earnings and asset value. The market in this scenario will likely value the stock based on some multiple of book value – you can guess which side of 1 this might be.

To attempt to average these two scenarios will fail. Investors will then have a tendency to be short the stock when it is going up and long when it is going down. Just ask Bill Miller !

It is impossible to determine when, or indeed if, there will be a regime shift from inflows to outflows. The best that can be hoped is to observe when it happens and be prepared to move fast when it does.